Ted is the author of two new books: and

This video is an interview about his books and ministry.

Inertia is “a tendency to do nothing or to remain unchanged” or “a lack of activity especially when movement is needed.” Intellectual inertia is mental laziness and anti-intellectualism.

The Bible commands Christians to honor God “with all of our mind” (Mark 12:30). I suggest, however, that a profound inertia hinders many evangelicals from obeying this demand. Mental activity is desperately needed, but many Christians are unable or unwilling to embrace intellectual discipleship or to integrate faith and ideas according to the biblical worldview.

The inevitable result is the status quo, marginalization of the church, aversion to risk and entrepreneurialism, and worst of all, the restriction of evangelical Christianity to private emotionalism and cultural irrelevance. Where I live, the evangelical church has little impact upon the educated or elite, the university community, and the cultural gatekeepers. Many believers have ceded worldview dominion, popular culture, and public policy to secular power brokers.

Sadly, our intellectual sluggishness affects every aspect of Christian life and practice. It is “deliberate ignorance,” according to the theologian, John Frame. Why? Because the hegemony of the secular worldview fosters an anti-intellectual outlook that severely restricts faith and practice to the private, subjective, and behavioral realms. As a result, the biblical worldview is neither intellectually plausible nor existentially credible. And of course, God is not honored with our minds and his glory is not displayed in our ideas and practice. Evangelical Christians are complicit and culpable in this dilemma.

worldview fosters an anti-intellectual outlook that severely restricts faith and practice to the private, subjective, and behavioral realms. As a result, the biblical worldview is neither intellectually plausible nor existentially credible. And of course, God is not honored with our minds and his glory is not displayed in our ideas and practice. Evangelical Christians are complicit and culpable in this dilemma.

When we retreat from the world of ideas, theoretical analysis or cultural critique, how can we discern, for example, the relationship between faith and philosophy, conflicting truth claims and alternative worldviews, faith and science, political ideology and social advocacy, psychology and counseling, business and economics, education, the arts, and so forth?

In contrast, Frame declares that Christians have a God-given “stewardship of the mind and intellect.” He wrote:

It is remarkable that Christians so readily identify the lordship of Christ in matters of worship, salvation, and ethics, but not in thinking. But . . . God in Scripture over and over demands obedience of his people in matters of wisdom, thinking, knowledge, understanding, and so forth. (“A History of Western Philosophy and Theology,” p. 5)

Perhaps then, we should ask a few honest questions that promote intellectual self-awareness:

Are we personally afflicted with self-imposed intellectual inertia?

Is there inertia that hinders the gospel and limits the evangelical church, particularly in your culture?

What does it mean to “love God with all the mind” in your society, especially among cultural gatekeepers, such as the educated and elite classes?

I have been a Christian for more than fifty years. During this time, I have sung many of the same songs―over and over again. The choruses, especially, are problematic―and repetitive, so repetitive. Quite honestly, it is now boring.

It is boring, because our songs are often simply expressions of emotion: how we feel or what we experience. So often, the music is all about “me”: my needs, my emotions, my benefits in Christ.

(Watch this brief satire about “me worship,” using popular choruses with lyrics altered to highlight the “me focus”: “It’s All About Me.”)

It is boring, because so often the musical style is the same―light rock and pop music genres. Is it possible, however, to worship God with other musical genres: folk, classical, or jazz, for example?

It is boring, because so often the musical style is the same―light rock and pop music genres. Is it possible, however, to worship God with other musical genres: folk, classical, or jazz, for example?

It is boring, because many songs concern the experience of conversion, so they are too simple or shallow for mature believers. Could there be hymns about suffering, sanctification, or the perplexities of life or the demands of the gospel or our future in eternity?

It is boring, because there is so little doctrine or intellectual content. Could there be songs that echo the themes of the psalms or prayers of Paul or the deeper doctrines of the Bible? Could we rediscover some of the ancient and classic hymns of the church?

R. C. Sproul commented about contemporary worship, “We have passion―indeed hearts on fire for the things of God. But that passion must resist with intensity the anti-intellectual spirit of the world.” Similarly, Ethan Renow in his article, “The Tragedy of Dumbing-Down Christianity,” summarizes the issue quite well:

We are happy to float along the surface with a “Hillsong-deep theology” and call it good. And we wonder why people are leaving the Church in droves. A church that offers only emotional, feel-good theology is going to lose the long-term wrestling match to a well-read and convincing atheist nearly every time.

As a learning adventure, I urge you to review the table of contents of any classic hymnal, especially a Calvinist hymnbook. You will discover from the themes listed that our music had once been much deeper and broader―and beautiful.

For this reason, I thank God for the music ministries of Keith and Kristyn Getty and Sovereign Grace Music!

I recently heard about a conversation between a father and his son concerning theology. The son is a university student. He struggles with the non-Christian worldviews taught at the university. He told his father that he studies theology for answers. He said that an intellectual pursuit of God is an important part of serving God. In response, the father cited 1 Corinthians 8:1, where Paul writes that “knowledge puffs up” while “love builds up.” In effect, he counseled, “Son, we don’t need theology.”

This kind of bias against theology―and anti-intellectualism generally―sometimes appears among evangelicals, particularly among fundamentalists, charismatics, and Pentecostals. The assumption seems to be:

Too much thinking is dangerous.

Too much thinking about God is especially dangerous.

Studying theology is thinking about God too much.

Therefore, theology is dangerous and should be avoided. (It is boring too!)

I attended a charismatic church for many years that embraced this bias. True spirituality was expressed in the realm of feelings, subjectivity, and experience. Pastors who had less theological training were held in high regard. I never adapted to this setting, for I was always curious, always reading, and I even studied religion at a secular university! I was suspected as a source of harmful ideas.

Second, it is also important to define theology. Theology is simply the study of God’s revelation, derived from the Greek terms, theos, “God” and logos, (“-ology” or “word”). Theology means “words about God,” “the study of God,” or even “sound doctrine.” In this light, it is insightful to consider Paul’s command for thought leaders (pastors and teachers) in Titus 1:9, “He must hold firm to the trustworthy word as taught, so that he may be able to give instruction in sound doctrine [theology] and also to rebuke those who contradict it.”

instruction in sound doctrine [theology] and also to rebuke those who contradict it.”

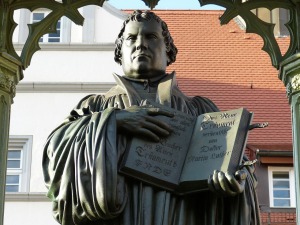

Third, it is extremely naive to minimize theology in the Christian life. The historical fact is that we stand upon the shoulders of theological giants, who formulated our precious statements of belief, like the Apostles Creed, Nicene Creed, or Westminster Confession of Faith. Whenever we speak of the Trinity, atonement, sovereignty, or Jesus Christ, for instance, we talk theology. We cannot avoid it. Remember, as well, that the great leaders of the church in the past were often well-trained, such as Augustine, Anselm, Calvin, Wesley, Abraham Kuyper, and C. S. Lewis. Tim Keller, who recently passed away, was an intellectual, theologian, and pastor. Many Christian leaders founded universities, led nations, and served as respected Christian spokesmen.

Finally, an undue fear or avoidance of theology is naive because it fails to recognize that ideas have consequences. I think one of clearest expressions of this reality is the statement of J. Gresham Machen, founder of Westminster Theological Seminary in 1921:

False ideas are the greatest obstacles to the reception of the Gospel. We may preach with all the fervor of a reformer and yet succeed in winning a straggler here and there, if we permit the whole collective thought of the nation or of the world to be controlled by ideas which, by the resistless force of logic, prevent Christianity from being regarded as anything more than a harmless delusion. Under such circumstances, what God desires us to do is to destroy the obstacle at its root….What is today a matter of academicspeculation begins to move tomorrow armies and pull down empires. In that second stage, it has gone too far to be combated; the time to stop it was when it was still a matter of impassioned debate. So as Christians we should try to mould the thought of the world in such a way as to make the acceptance of Christianity something more than a logical absurdity.

So, do we need theology? Yes!

Do theological ideas have consequences? Yes!

Should Christians understand what they believe? Yes!